By NIMMI RAGHUNATHAN

ORANGE, CA - Amardeep Singh is nothing if not passionate – not of the rabble rousing variety; but in the measured, first-hand witness kind of way. Through his travels and study of the scriptures, he is convinced of the beauty of a tolerant and expansive world. The acme of human endeavors - his approach indicates –

ORANGE, CA - Amardeep Singh is nothing if not passionate – not of the rabble rousing variety; but in the measured, first-hand witness kind of way. Through his travels and study of the scriptures, he is convinced of the beauty of a tolerant and expansive world. The acme of human endeavors - his approach indicates –

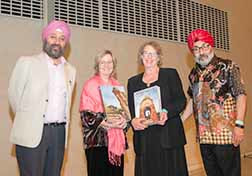

is to be measured through unifying art forms and architecture. At the Fish Interfaith Center at Chapman University here, on April 16, the Singapore based author made a strong case for inclusiveness without having to eschew the uniqueness of a culture or the traditions of a faith. Central to his talk, were his two lavishly photographed coffee table books, “Lost Heritage – The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan” and its newly published sequel, “The Quest Continues – Lost Heritage, The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan.” The works which draw attention to his religion and its history brought interested SoCal members to the event organized by Sikhlens as part of its Baisakhi celebrations.

Singh’s premise is remarkable in its simplicity: the empire of Ranjit Singh stretched from Afghanistan to Punjab in India; it is inconceivable that it does not have a legacy that is larger than the modern perception where the Sikh is equated just with Punjab and the Punjabi language. With roughly 80 percent of that erstwhile empire now in Pakistan, and no access to the culture that once flowered there, Singh fears that the modern Sikh is forgetting his heritage; one of deep spirituality and syncretism.

His talk featured images of gurdwaras and forts of centuries ago as well as the living legacy of those who still practice the faith in Pakistan. He spoke of the 15,000-odd Pashtun Sikhs who lead respectable lives along the Afghan border – speaking no Punjabi but adhering to the faith. He also pointed out there were and are, Sikhs who communicate best in the Urdu language, proving that language cannot be associated with religion. Making his case that Sikhs are more than the dominant Khalsa of today, he posited there are at least a million people who believe in the teachings of Guru Nanak, declaring, “they deserve the attention of the world.” Reeling off the names of a number of other groups that are not typically embraced - the Nanakpanthis, Udasis, Nirmalas, among them – he argued, “when we define ourselves, we reject others.” In sum, Singh would like the Sikh of today to have a bigger world view shaking off uniformity, linguistic limitations and narrow geography.

Showing pictures of frescoes from crumbling gurdwaras he pushed for the understanding of Guru Nanak’s teachings as an inclusive one. The art of the time depicts the spiritual master with his traveling companion Baba Farid; a representation he said, that is difficult to find in today’s Punjab. “Baba Farid was a Sufi, but he is yours, he is me, he is in my scripture,” Singh asserted.

From his travels he showed pictures of the shrine of Hazrat Shah Shams Tabrez where he spotted names of visitors scrawled in Gurmukhi; and in the decrepit former gurdwaras he noted the architectural unity. Jogging the collective memory, he said before 1947 Muslims had sung inside the Golden Temple; indeed in Pakistan, he found a family that still keeps up the tradition that has been handed down to them, singing keertan at a gurdwara that is barely visited.

Singh is a child of India’s partition of 1947. His father moved from what is now Pakistan Occupied Kashmir to Uttar Pradesh; never forgetting his roots and making an impression on his son. Singh is also an accidental author. His first book across 36 cities and villages in Pakistan was born out of his desire to trace his father’s recollections. The second took him across PoK, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Pakistani Punjab.

In the concluding segment of the evening, Singh took questions from the audience.

Painting

The event, emceed by Pavneet Mac also featured the paintings of Texas based artist Jasmeet Kaur who specializes in visualizing through nature and abstraction, the spirituality and tranquility of the scriptures. Proceeds from the canvases she displayed at the event were also earmarked to go toward the scholarship and the student travel program that Sikhlens has supported for several years now.

Others who spoke were Gail J. Stearns Dean of the Wallace All Faiths Chapel and Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Chapman University; Reverend Nancy Brink is the Director of Church Relations at Chapman University who spoke of the trip that students took to India and the great impact Amritsar and the langar at the Golden Temple had on the group. The evening concluded with a catered Indian dinner.

Singh’s premise is remarkable in its simplicity: the empire of Ranjit Singh stretched from Afghanistan to Punjab in India; it is inconceivable that it does not have a legacy that is larger than the modern perception where the Sikh is equated just with Punjab and the Punjabi language. With roughly 80 percent of that erstwhile empire now in Pakistan, and no access to the culture that once flowered there, Singh fears that the modern Sikh is forgetting his heritage; one of deep spirituality and syncretism.

His talk featured images of gurdwaras and forts of centuries ago as well as the living legacy of those who still practice the faith in Pakistan. He spoke of the 15,000-odd Pashtun Sikhs who lead respectable lives along the Afghan border – speaking no Punjabi but adhering to the faith. He also pointed out there were and are, Sikhs who communicate best in the Urdu language, proving that language cannot be associated with religion. Making his case that Sikhs are more than the dominant Khalsa of today, he posited there are at least a million people who believe in the teachings of Guru Nanak, declaring, “they deserve the attention of the world.” Reeling off the names of a number of other groups that are not typically embraced - the Nanakpanthis, Udasis, Nirmalas, among them – he argued, “when we define ourselves, we reject others.” In sum, Singh would like the Sikh of today to have a bigger world view shaking off uniformity, linguistic limitations and narrow geography.

Showing pictures of frescoes from crumbling gurdwaras he pushed for the understanding of Guru Nanak’s teachings as an inclusive one. The art of the time depicts the spiritual master with his traveling companion Baba Farid; a representation he said, that is difficult to find in today’s Punjab. “Baba Farid was a Sufi, but he is yours, he is me, he is in my scripture,” Singh asserted.

From his travels he showed pictures of the shrine of Hazrat Shah Shams Tabrez where he spotted names of visitors scrawled in Gurmukhi; and in the decrepit former gurdwaras he noted the architectural unity. Jogging the collective memory, he said before 1947 Muslims had sung inside the Golden Temple; indeed in Pakistan, he found a family that still keeps up the tradition that has been handed down to them, singing keertan at a gurdwara that is barely visited.

Singh is a child of India’s partition of 1947. His father moved from what is now Pakistan Occupied Kashmir to Uttar Pradesh; never forgetting his roots and making an impression on his son. Singh is also an accidental author. His first book across 36 cities and villages in Pakistan was born out of his desire to trace his father’s recollections. The second took him across PoK, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Pakistani Punjab.

In the concluding segment of the evening, Singh took questions from the audience.

Painting

The event, emceed by Pavneet Mac also featured the paintings of Texas based artist Jasmeet Kaur who specializes in visualizing through nature and abstraction, the spirituality and tranquility of the scriptures. Proceeds from the canvases she displayed at the event were also earmarked to go toward the scholarship and the student travel program that Sikhlens has supported for several years now.

Others who spoke were Gail J. Stearns Dean of the Wallace All Faiths Chapel and Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Chapman University; Reverend Nancy Brink is the Director of Church Relations at Chapman University who spoke of the trip that students took to India and the great impact Amritsar and the langar at the Golden Temple had on the group. The evening concluded with a catered Indian dinner.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed