By MEDHA RAJ

REDONDO BEACH, CA – The star of veteran Bollywood actress Hema Malini glittered on, at the Redondo Beach Performing Arts Center on July 6 in the dance ballet ‘Durga’. With brilliant set design and immaculate costuming, the show seamlessly weaved together the stories of the Mother Goddess as Sati, Parvati,

REDONDO BEACH, CA – The star of veteran Bollywood actress Hema Malini glittered on, at the Redondo Beach Performing Arts Center on July 6 in the dance ballet ‘Durga’. With brilliant set design and immaculate costuming, the show seamlessly weaved together the stories of the Mother Goddess as Sati, Parvati,

and Durga with the interplay of Sanskrit chants, occasional Hindi dialog, and filmy, upbeat music composed by the famed Ravindra Jain. Combined with props, vivid backdrops, and cleverly-designed lighting, ‘Durga’ played out like a piece of Bollywood cinema and the audience, tuned to the latest mythological Hindi television programming, responded enthusiastically.Viewing the famous tale executed in such rich detail, the crowd sighed at Sati’s sacrifice, applauded the union of Siva and Parvati, and cheered at Durga’s defeat of Mahishasura.

The performance opened with Hema Malini as Sati, performing with a full court of 16 dancers. If the backdrop of Kailash with a seated Sati and Shiva in the foreground and the rendering of the ‘Ardhanariswara Stotram’ was enough to set the mood for the devout in the audience, for the uninitiated it quite simply provided a stunning visual.

The twirling scene of bright hues and gold fabrics in Daksha’s palace was followed by a duet between Hema Malini and a commanding Shiva (Madhavapeddi Murthy). Her ultimate sacrifice of self-immolation was artfully choreographed, as the stage glowed bright red with images of tall flames while the dancers performed the thunderous scene engulfing Sati.

Hema Malini’s subsequent transformation into a patient Parvati waiting in all seasons for Shiva to notice her was marked by audiovisual pageantry. In the monsoons, she’s met by six blue and silver dancers in wispy fabrics, performing a lilting dance to match the background images and sounds of a rolling thunderstorm. In the spring, her green and gold dancers flit past a backdrop of flowers shaking in a windy meadow, large tulips in hand. The changing seasons enchanted through the choreographer’s meaningful attention to detail. The final union of Shiva and Parvati was marked by equal grandeur, as performers threw flowers and Nandi danced in a golden-hewed set.

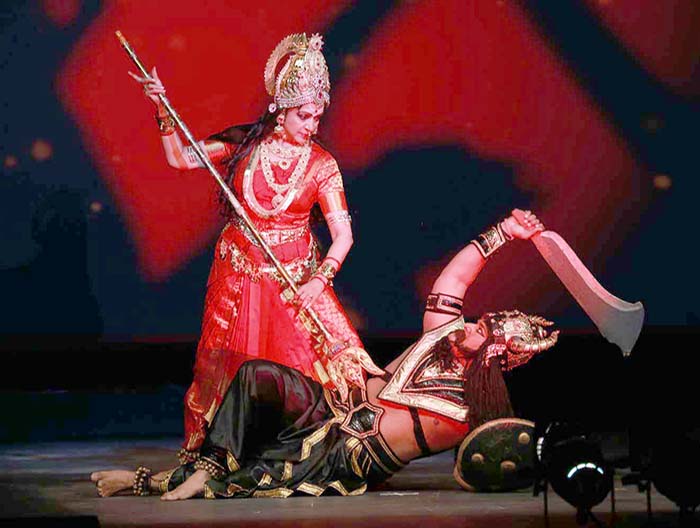

The second half of the show focused on the battle between the goddess and the demon. A foot-stomping, roaring Mahishasura danced with frighteningly masked assistants in his dark palace to music thick with heavy drums. The dancers in the heavens, by contrast, were light on their feet, narrating the creation of Durga.

The most striking scene in the dance ballet was of Durga receiving weaponry for her fight against Mahishasura. Malini stood—clad in shining jewels and characteristic red sari—in front of a line of dancers holding swords, maces, and conches. It created a dramatic silhouette of a fearsome Durga and shifted the performance’s tone through the final, loud battle scene where dancers dashed in and out of the stage as she killed the asura. The sheer spectacle of ‘Durga’ was captivating. Still, a flaw remained between the color coordinated costumes and dazzling audiovisuals. ‘Durga’ straddled an awkward line, neither classical in its outlook, nor conscious of its odd assortment of Indian dance traditions. Rati and Kamadeva briefly attempted foot-stomping Kathak; Mahishasura’s aides donned Mohiniattam’s garb; Bharatanatyam made the occasional appearance; and—save for Shiva—the dancers collectively performed a shiftless, meandering style of Kuchipudi. The plausibility of Malini being capable of—even fictitiously—wounding Mahishasura diminished with each of her expressionless and soft-footed strides across the stage.

Ultimately, though distinctly Bollywood in appearance and sound, ‘Durga’ served its purpose: to tell a well-known tale to a rapt crowd and remind the audience of Hema Malini’s interminable glamour. That she is also a Member of Parliament from the ruling BJP gave her presence added weight. At the top of the program, a brief film played with India’s home, finance and other ministers celebrating her U.S. tour and hailing her as India’s cultural ambassador.

The well received event was brought to the Southland by Rashmi Shah who spoke of his humble roots and the Shah Foundation, his charity organization, and Babubhai Patel of Neema Sari Palace who lauded Hema Malini’s BJP connections.

The performance opened with Hema Malini as Sati, performing with a full court of 16 dancers. If the backdrop of Kailash with a seated Sati and Shiva in the foreground and the rendering of the ‘Ardhanariswara Stotram’ was enough to set the mood for the devout in the audience, for the uninitiated it quite simply provided a stunning visual.

The twirling scene of bright hues and gold fabrics in Daksha’s palace was followed by a duet between Hema Malini and a commanding Shiva (Madhavapeddi Murthy). Her ultimate sacrifice of self-immolation was artfully choreographed, as the stage glowed bright red with images of tall flames while the dancers performed the thunderous scene engulfing Sati.

Hema Malini’s subsequent transformation into a patient Parvati waiting in all seasons for Shiva to notice her was marked by audiovisual pageantry. In the monsoons, she’s met by six blue and silver dancers in wispy fabrics, performing a lilting dance to match the background images and sounds of a rolling thunderstorm. In the spring, her green and gold dancers flit past a backdrop of flowers shaking in a windy meadow, large tulips in hand. The changing seasons enchanted through the choreographer’s meaningful attention to detail. The final union of Shiva and Parvati was marked by equal grandeur, as performers threw flowers and Nandi danced in a golden-hewed set.

The second half of the show focused on the battle between the goddess and the demon. A foot-stomping, roaring Mahishasura danced with frighteningly masked assistants in his dark palace to music thick with heavy drums. The dancers in the heavens, by contrast, were light on their feet, narrating the creation of Durga.

The most striking scene in the dance ballet was of Durga receiving weaponry for her fight against Mahishasura. Malini stood—clad in shining jewels and characteristic red sari—in front of a line of dancers holding swords, maces, and conches. It created a dramatic silhouette of a fearsome Durga and shifted the performance’s tone through the final, loud battle scene where dancers dashed in and out of the stage as she killed the asura. The sheer spectacle of ‘Durga’ was captivating. Still, a flaw remained between the color coordinated costumes and dazzling audiovisuals. ‘Durga’ straddled an awkward line, neither classical in its outlook, nor conscious of its odd assortment of Indian dance traditions. Rati and Kamadeva briefly attempted foot-stomping Kathak; Mahishasura’s aides donned Mohiniattam’s garb; Bharatanatyam made the occasional appearance; and—save for Shiva—the dancers collectively performed a shiftless, meandering style of Kuchipudi. The plausibility of Malini being capable of—even fictitiously—wounding Mahishasura diminished with each of her expressionless and soft-footed strides across the stage.

Ultimately, though distinctly Bollywood in appearance and sound, ‘Durga’ served its purpose: to tell a well-known tale to a rapt crowd and remind the audience of Hema Malini’s interminable glamour. That she is also a Member of Parliament from the ruling BJP gave her presence added weight. At the top of the program, a brief film played with India’s home, finance and other ministers celebrating her U.S. tour and hailing her as India’s cultural ambassador.

The well received event was brought to the Southland by Rashmi Shah who spoke of his humble roots and the Shah Foundation, his charity organization, and Babubhai Patel of Neema Sari Palace who lauded Hema Malini’s BJP connections.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed