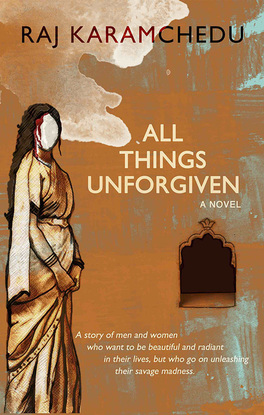

In the volatile interior of Old Hyderabad, where the majestic tops of its extraordinary mosques stick out into the serene skies, lives a south Indian family, steadily descending into ruin. Passionate and ambitious Anasuya dreams of bettering her education, but when she discovers her husband’s affair, she is consumed by a desire to exact revenge. Bright and joyful Rushi, brimming with resolutions and desires,

believes in loving all humanity. But in a moment of frenzy he nearly kills his wife. Growing up in this oppressive midst is their son, the spirited, sensitive Arya, unwavering in his love for them, but who from early on develops disturbing tendencies.

And when Arya, having left for America as a young man filled with shame, returns home in a troubled state, everyone’s lives are changed forever. Immersing the reader in cultural and moral dilemmas of modern India, ‘All Things Unforgiven’ by Raj Karamchedu is an unsettling debut novel that depicts the whole of this South Indian family and charts their descent into oppression and violence - and their strivings for forgiveness and love. Here is what he had to say:

Q: Much of All Things Unforgiven takes place in Old Hyderabad. And Hyderabad itself is emerging as an important tech city. What is it like there?

A: The old city, as it is usually called, is worlds apart from the “high-tech city” that emerged in a different part of Hyderabad. In the old city a strong blend of Muslim and Hindu cultures exists, with mosques, temples, great bazaars, and narrow, congested streets. Birds and color and Irani cafes are everywhere in the old city. I used to walk everyday through these streets, from my house to a bus stop at Charminar to go to school. I never thought too much of it when I was growing up there, but a great and glorious tradition and culture pervades all over the old city: Iranian cafes that serve a special Hyderabad tea, shops that sell jewelry, gold, perfume (old city is famous for it) colorful textiles, a mindboggling variety of spices. Two major languages spoken are Urdu (a variant of it actually, mixed with Hindi) and Telugu.

Q: What was your childhood and family life like there?

A: Loud, noisy, emotional, intense, boisterous, the house always full of people: that’s how I remember growing up. Ours was a middle-class family, or maybe lower middle-class even. The radio was always on. My mother was a strong, loud and passionate woman. Dad liked Urdu classical music, and qawwali (Sufi traditional music). Interesting thing about my father was, I don’t remember him being a particularly strong, always-there-for-you father, but somehow he always inspired me by the way his friends and colleagues talked about him. He was a civil engineer. Ours was a very traditional Hindu family, but my parents weren’t strict. Dad worked and mom stayed home. Large families, on both sides. In many ways my early years were similar to how and what I describe in the book.

Q: How are gender roles described in All Things Unforgiven? How common are these roles right now in Indian society?

A. These roles are quite common now. Indian society doesn’t evolve much - though the cities will make you think it is evolving. Caste-based discrimination, deeply rooted violence on women and on children and on other caste people, are still the norms.

In the novel, I wanted to show how judgments, both explicit and subtle, on women are made in a Telugu family; and how the seeds of violence in such a family are rooted in such judgments. In Telugu culture, I know this to be true of other Indian cultures as well, everyone behaves as though only lower-caste families, not them, treated women as second-class souls. But, looking back at how life was in such a family, it occurred to me that there was something odd about how we (we, as in the privileged Brahmin-caste folks) treated our mothers, our wives, and our women.

As I became more self-aware, it became clear to me that in such families we boys and men were no different from the so-called lower-caste families. We too routinely pronounced women in our lives guilty, disapproved their expression, and behaved as though they were in a compartment of their own. We drew and guarded the boundary lines of their existence. All this while we loved them deeply, felt for them, and felt the intense pain of separation from them.

Q: A few years ago you launched Saaranga Books. What inspired you? What is Saaranga’s mission?

A. Five years ago I accidentally discovered a Telugu blog and that revived the memory of all my Telugu reading days. I used to read Telugu literature a lot when I was in India. I was depressed to see that nothing had changed in most Telugu literature; it is the same absence of quality literary criticism, the same dominance of pulp fiction. I wanted to change that. Hence Saaranga.

Q: You’re also the translator of some Telugu poetry for a forthcoming collection, The Oxford Anthology of Telugu Dalit Poems (Oxford University Press, 2015). To what does “Telugu Dalit” refer?

A: Dalit refers to a certain identity of millions of people in India. Dalits are treated as untouchables, the lowest caste people. Dalits are not specific to Telugu, but this collection deals specifically with Telugu Dalits. Due to tradition and history and rigid caste system, they have always been discriminated by the upper caste people across India, especially the upper caste Brahmin people. Violence is perpetrated on them on a routine basis.

And when Arya, having left for America as a young man filled with shame, returns home in a troubled state, everyone’s lives are changed forever. Immersing the reader in cultural and moral dilemmas of modern India, ‘All Things Unforgiven’ by Raj Karamchedu is an unsettling debut novel that depicts the whole of this South Indian family and charts their descent into oppression and violence - and their strivings for forgiveness and love. Here is what he had to say:

Q: Much of All Things Unforgiven takes place in Old Hyderabad. And Hyderabad itself is emerging as an important tech city. What is it like there?

A: The old city, as it is usually called, is worlds apart from the “high-tech city” that emerged in a different part of Hyderabad. In the old city a strong blend of Muslim and Hindu cultures exists, with mosques, temples, great bazaars, and narrow, congested streets. Birds and color and Irani cafes are everywhere in the old city. I used to walk everyday through these streets, from my house to a bus stop at Charminar to go to school. I never thought too much of it when I was growing up there, but a great and glorious tradition and culture pervades all over the old city: Iranian cafes that serve a special Hyderabad tea, shops that sell jewelry, gold, perfume (old city is famous for it) colorful textiles, a mindboggling variety of spices. Two major languages spoken are Urdu (a variant of it actually, mixed with Hindi) and Telugu.

Q: What was your childhood and family life like there?

A: Loud, noisy, emotional, intense, boisterous, the house always full of people: that’s how I remember growing up. Ours was a middle-class family, or maybe lower middle-class even. The radio was always on. My mother was a strong, loud and passionate woman. Dad liked Urdu classical music, and qawwali (Sufi traditional music). Interesting thing about my father was, I don’t remember him being a particularly strong, always-there-for-you father, but somehow he always inspired me by the way his friends and colleagues talked about him. He was a civil engineer. Ours was a very traditional Hindu family, but my parents weren’t strict. Dad worked and mom stayed home. Large families, on both sides. In many ways my early years were similar to how and what I describe in the book.

Q: How are gender roles described in All Things Unforgiven? How common are these roles right now in Indian society?

A. These roles are quite common now. Indian society doesn’t evolve much - though the cities will make you think it is evolving. Caste-based discrimination, deeply rooted violence on women and on children and on other caste people, are still the norms.

In the novel, I wanted to show how judgments, both explicit and subtle, on women are made in a Telugu family; and how the seeds of violence in such a family are rooted in such judgments. In Telugu culture, I know this to be true of other Indian cultures as well, everyone behaves as though only lower-caste families, not them, treated women as second-class souls. But, looking back at how life was in such a family, it occurred to me that there was something odd about how we (we, as in the privileged Brahmin-caste folks) treated our mothers, our wives, and our women.

As I became more self-aware, it became clear to me that in such families we boys and men were no different from the so-called lower-caste families. We too routinely pronounced women in our lives guilty, disapproved their expression, and behaved as though they were in a compartment of their own. We drew and guarded the boundary lines of their existence. All this while we loved them deeply, felt for them, and felt the intense pain of separation from them.

Q: A few years ago you launched Saaranga Books. What inspired you? What is Saaranga’s mission?

A. Five years ago I accidentally discovered a Telugu blog and that revived the memory of all my Telugu reading days. I used to read Telugu literature a lot when I was in India. I was depressed to see that nothing had changed in most Telugu literature; it is the same absence of quality literary criticism, the same dominance of pulp fiction. I wanted to change that. Hence Saaranga.

Q: You’re also the translator of some Telugu poetry for a forthcoming collection, The Oxford Anthology of Telugu Dalit Poems (Oxford University Press, 2015). To what does “Telugu Dalit” refer?

A: Dalit refers to a certain identity of millions of people in India. Dalits are treated as untouchables, the lowest caste people. Dalits are not specific to Telugu, but this collection deals specifically with Telugu Dalits. Due to tradition and history and rigid caste system, they have always been discriminated by the upper caste people across India, especially the upper caste Brahmin people. Violence is perpetrated on them on a routine basis.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed